I can’t believe it’s been eight years since having traveled to Italy for the three-month volunteer trip that kick-started my career (and this blog). Reflecting on some of my original posts, it simultaneously fees like yesterday and a lifetime ago. Each message holds strong, though; I’m so grateful for all I learned (and am able to apply in my work every day) during my time in VV.

Below is one of my original posts from September of 2014. Re-sharing as I reminisce.. 🙂

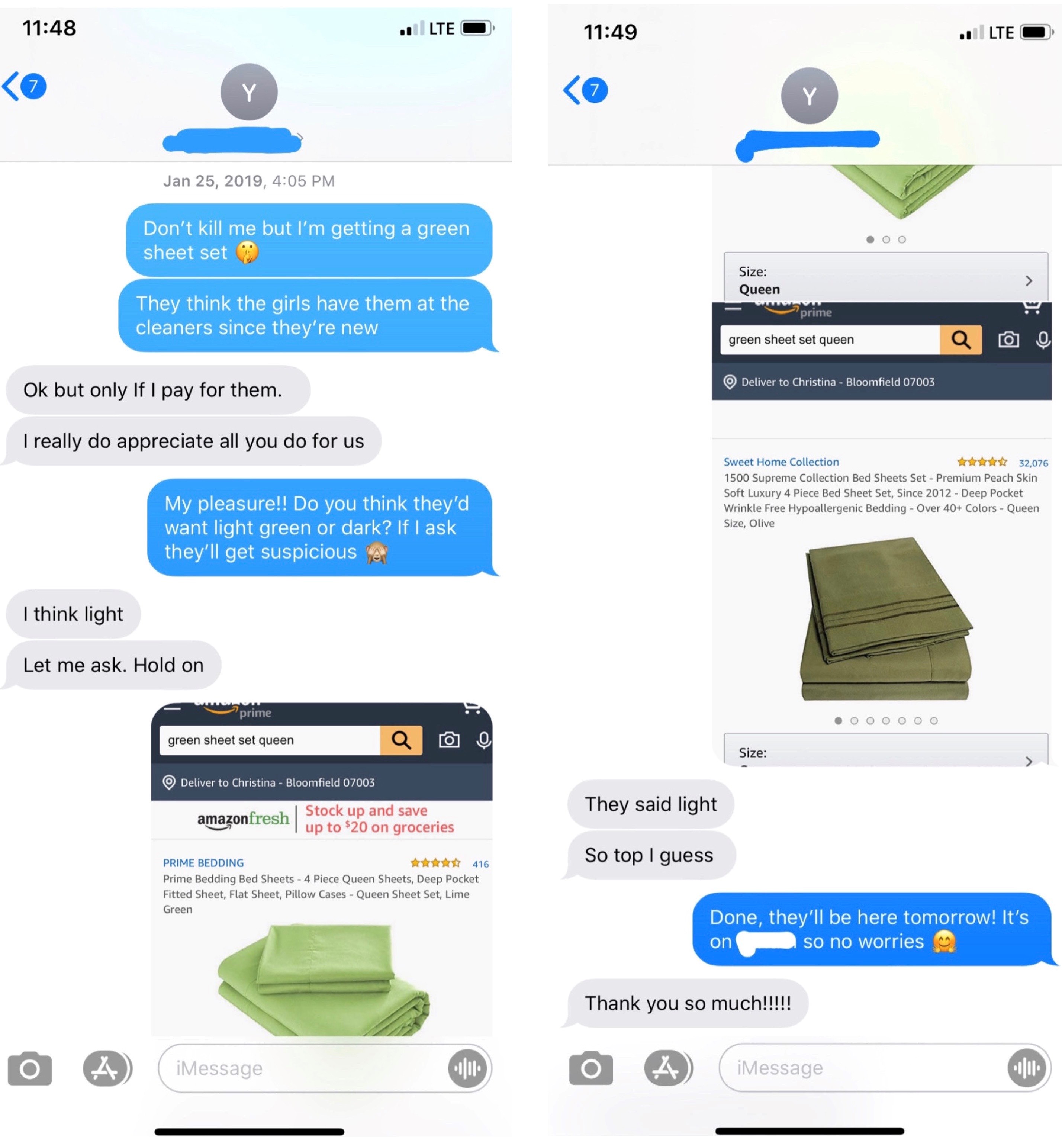

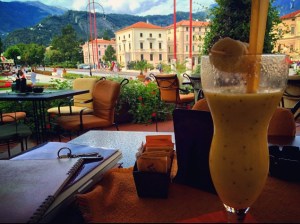

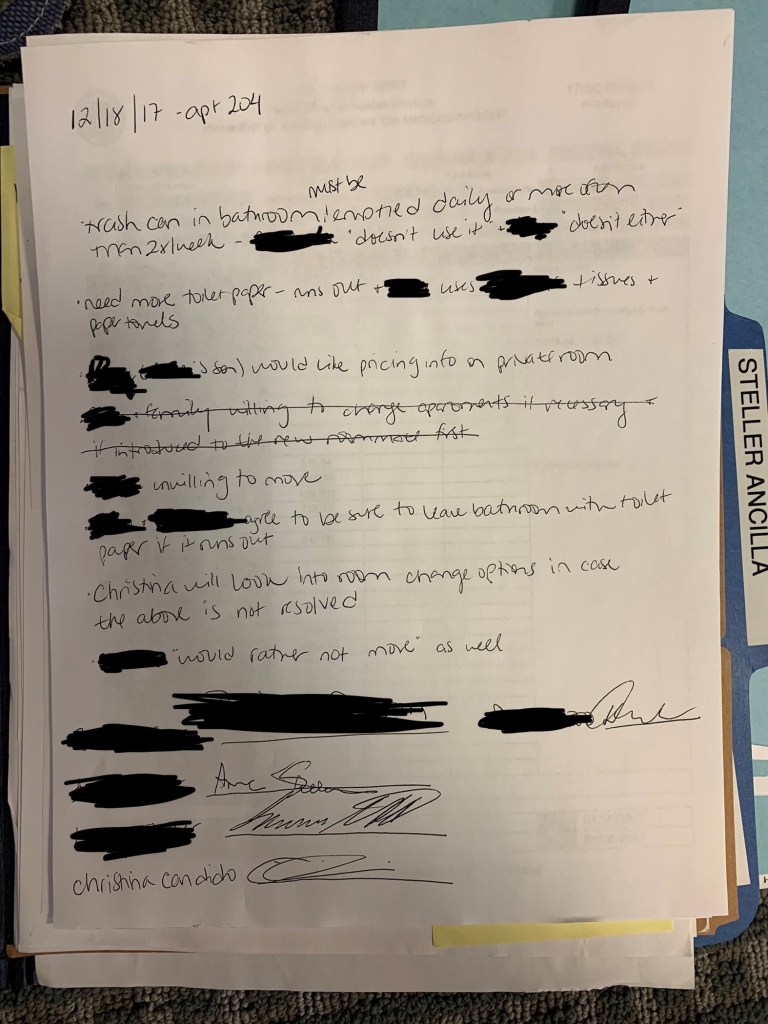

As I’m taking notes from work today, I can’t help but sneak a picture of where I’m writing:

I am so in love with this town (& with Italy in general)! Though I studied abroad in Rome and have been back since, I still find myself struggling with the language; when you don’t use it for a while, you definitely start to forget! Thank God for iPhone apps and Google translate :-O

Working with my loves, I’m realizing, requires me to learn and practice two languages: that of Northern Italy and of Alzheimer’s disease. The latter is more complex and multifaceted than even the most ridiculous Italian verb conjugations.

In one of many insightful essays, Dr. Taylor writes:

“If I call you “Mom” or “Dad,” I am probably not confusing you with my mom or dad; I know they are dead. I may be thinking about the feelings and behaviors I associate with mom and dad. I miss those feelings; I need them. It’s just that I so closely associate those feelings with my mom and dad that the words I use become interchangeable when I talk about them. I don’t take the time or I can’t or won’t make the distinction between the people and the feelings.”

Similarly, Dr. Robbins goes on to stress that:

“Almost always, though, what’s said in the moment does NOT reflect how the person with dementia has always thought.”

Not only are we listening to (and, in my case, translating) what’s being said, we must also attempt to decipher its true meaning. Much like learning Italian, this requires patience and practice coupled with both empathy and understanding.

My phone can help me hold a conversation, but not to interpret unspoken messages. Aside from the always-entertaining hand gestures, most of what I’ve had to learn in Italian is verbal/written. The language of Alzheimer’s, however, is often primarily unspoken.

According to Bob DeMarco, when spending time with his mom it’s important for him to “speak the local language.”

“Eventually I realized I was drowning my mother with too many words. Sometimes, all I needed to do was smile. Or put my arm around her shoulder and my head on her head. Instead of a long explanation about what we were going to do (like go to the bathroom before lunch), I’d stick out my hand and say, ‘Let’s go.’ And she’d come along willingly, even before asking, ‘Where are we going?’ To which I’d just smile and say, ‘To have fun.’”

In my experience, it’s the nonverbal that has been most powerful. It’s the smiling, hugging, kissing (often on the mouth 😐 why do Italian nonnas and nonnos LOVE to kiss on the mouth?!?!), and just being together that have sparked incredible responses and opened seemingly glued-shut doors. It’s the respect, patience, and empathy.. the looking up instead of talking down.. the face-to-face instead of over-the-shoulder.. these are what I’ve seen to brighten days and open flood gates.